Is Deep Reinforcement Learning Really Superhuman on Atari?

This post describes our recent work on Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) on the Atari benchmark. DRL appears today as one of the closest paradigm to Artificial General Intelligence and large progress in this field has been enabled by the popular Atari benchmark. However, training and evaluation protocols on Atari vary across papers leading to biased comparisons, difficulty in reproducing results and in estimating the true contributions of the methods. Here we attempt to mitigate this problem with SABER: a Standardized Atari BEnchmark for general Reinforcement learning algorithms. SABER allows us to compare multiple methods under the same conditions against a human baseline and to note that previous claims of superhuman performance on DRL do not hold. Finally, we propose a new state-of-the-art algorithm R-IQN combining Rainbow with Implicit Quantile Networks (IQN). Our code is available.

Deep Reinforcement Learning is a learning scheme based on trial-and-error in which an agent learns an optimal policy from its own experiments and a reward signal. The goal of the agent is to maximize the sum of future accumulated rewards and thus the agent needs to think about sequences of actions rather than instantaneous ones. The Atari benchmark is valuable for evaluating general AI algorithms as it includes more than 50 games displaying high variability in the task to solve, ranging from simple paddle control in the ball game Pong to complex labyrinth exploration in Montezuma’s Revenge which remains unsolved by general algorithms up to today.

We notice however that training and evaluation procedures on Atari can be different from paper to paper and thus leading to bias in comparison. Moreover this leads to difficulties to reproduce results of published works as some training or evaluation parameters are barely explained or sometimes not mentioned. In order to facilitate reproducible and comparable DRL, we introduce SABER: a Standardized Atari BEnchmark for general Reinforcement learning algorithms. Furthermore, we introduce a human world record baseline and argue that previous claims of superhuman performance of DRL might not hold. Finally, we propose a new state-of-the-art algorithm R-IQN by combining the current state-of-the-art Rainbow (Hessel et al., 2018) along with Implicit Quantile Networks (IQN (Dabney et al., 2018)). We release an open-source implementation of distributed R-IQN following the ideas from Ape-X!

DQN’s human baseline vs human world record on Atari Games

A common way to evaluate AI for games is to let agents compete against the best humans. Recent examples for DRL include the victory of AlphaGo versus Lee Sedol for Go, OpenAI Five on Dota 2 or AlphaStar versus Mana for StarCraft 2. For this reason one of the most used metrics for evaluating RL agents on Atari is to compare them to the human baseline introduced in DQN.

Previous works use the normalized human score, i.e., 0% is the score of a random player and 100% is the score of the human baseline, which allows one to summarize the performance on the whole Atari set in one number, instead of individually comparing raw scores for each of the 61 games. However we argue that this human baseline is far from being representative of the best human player, which means that using it to claim superhuman performance is misleading.

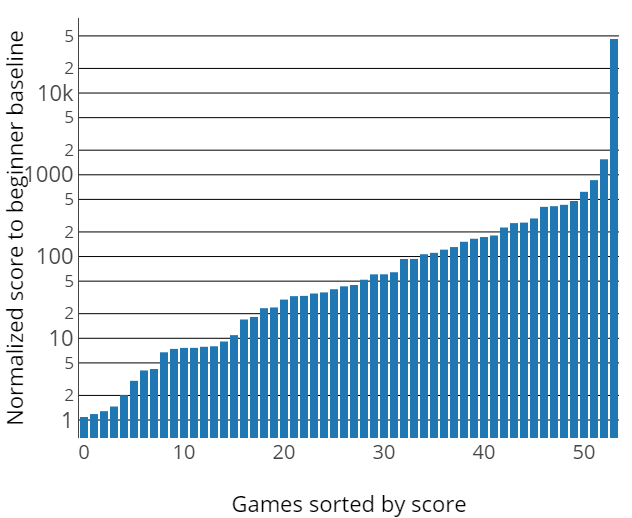

The current world records are available online for 58 of the 61 evaluated Atari games. For example, on VideoPinball, the world record is 50,000 times higher than the human baseline of DQN. Evaluating these world records scores using the usual human normalized score has a median of 4,400% and a mean of 99,300% (see Figure below for details on each game), to be compared to 200% and 800% of the current state-of-the-art Rainbow!

We estimate that evaluating the algorithms under the world record baseline instead of the DQN human baseline will give a better view of the gap remaining between best human players and DRL agents. Results are confirming this, as Rainbow reaches only a median human-normalized score of 3% (see Figure 2 below) meaning that for half of Atari games, the agent doesn’t even reach 3% of the way from random to best human run.

In the video below we analyze agents previously claimed as above human-level but far from the world record. By taking a closer look at the AI playing, we discovered that on most of Atari games DRL agents fail to understand the goal of the game. Sometimes they just don’t explore other levels than the initial one, sometimes they are stuck in a loop giving small amount of reward, etc. A compelling example of this is the game Riverraid. In this game, the agent must shoot everything and take fuel to survive: the agent dies if there is a collision with an enemy or if out of fuel. But as shooting fuel actually gives points, the agent doesn’t understand that he could play way longer and win even more points by actually taking this fuel bonus and not shooting them!

SABER: a Standardized Atari BEnchmark for general Reinforcement learning algorithms

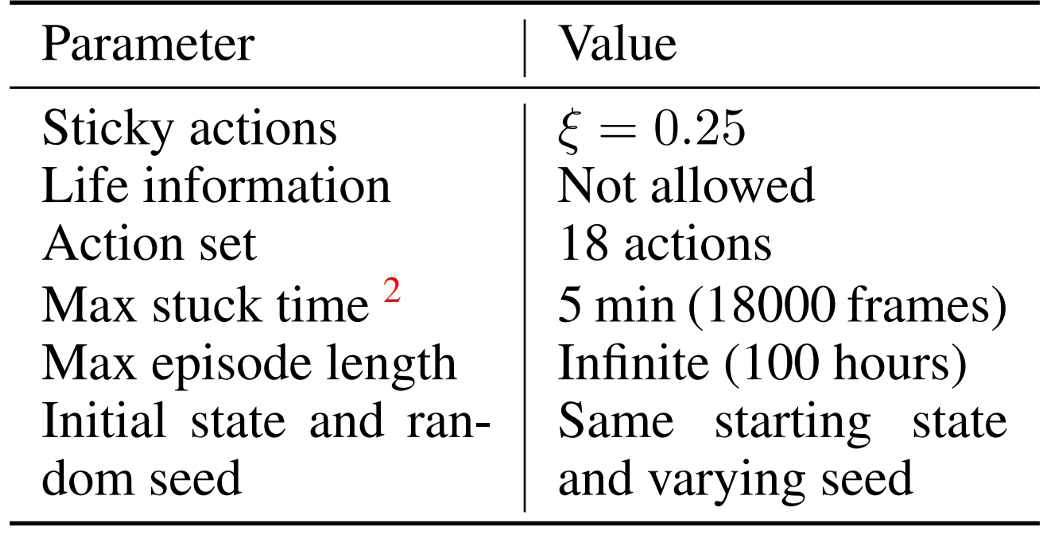

In our work we extend the recommendations proposed by (Machado et al., 2018) They also point out divergences in training and evaluating agents on Atari. Consequently they compile and propose a set of recommendations for more reproducible and comparable RL including sticky actions, ignoring life signal and using full action set.

There is however one major parameter that is left out in (Machado et al., 2018): the maximum number of frames allowed per episode. This parameter ends the episode after a fixed number of time steps even if the game is not over. In most of the recent works, this is set to 30 min of game play (i.e., 108k frames) and only to 5 min in some others (i.e.,18k frames). This means that the reported scores can not be compared fairly. For example, in easy games (e.g., Atlantis), the agent never dies and the score is more or less linear with the allowed time: the reported score will be 6 times higher if capped at 30 minutes instead of 5 minutes.

Another issue with this time cap comes from the fact that some games are designed for much longer gameplay than 5 or 30 minutes. On those games (e.g., Atlantis, Video Pinball, Enduro) the scores reported of Ape-X, Rainbow and IQN are almost the same. This is due to all agents reaching the time limit and getting the maximum possible score in 30 minutes: the difference in scores is due to minor variations, not algorithmic difference and thus the comparison is not significant. As a consequence, the more successful agents are, the more games are incomparable because they reach the maximum possible score in the time cap while still being far behind human world record.

This parameter can also be a source of ambiguity and error. The best score on Atlantis (2,311,815) is reported by Proximal Policy Optimization by (Schulman et al., 2017), however this score is likely wrong: it seems impossible to reach in 30 minutes only! The first distributional paper by (Bellemare et al.) also did this mistake and reported wrong results before adding an erratum in a later version on ArXiv (Bellemare et al., 2017).

We first re-implemented the current state-of-the-art Rainbow and evaluated it on SABER. We noticed that the same algorithm under different evaluation settings can lead to significantly different results. This showed again the necessity of a common and standardized benchmark, more details can be found in the paper.

Then we implemented a new algorithm, R-IQN, by replacing the C51 algorithm (which is one of the 6 components of Rainbow) by Implicit Quantile Network (IQN). Both C51 and IQN belong to the field of Distributional RL which aims to predict the full distribution of the Q-value function instead of just predicting the mean of it. The fundamental difference between these two algorithms is how they parametrize the Q-value distribution. C51, which is the first algorithm of Distributional RL, approximates the Q-value as a categorical distribution with fixed support and just learns the mass to attribute to each category. On the other hand, IQN approximates the Q-value with quantile regression and both the support and the mass arelearned resulting in a major improvement in performance and data-efficiency over C51. As IQN arises much better performance than C51 while still designed for the same goal (predict the full distribution of the Q-function), combining Rainbow with IQN is relevant and natural.

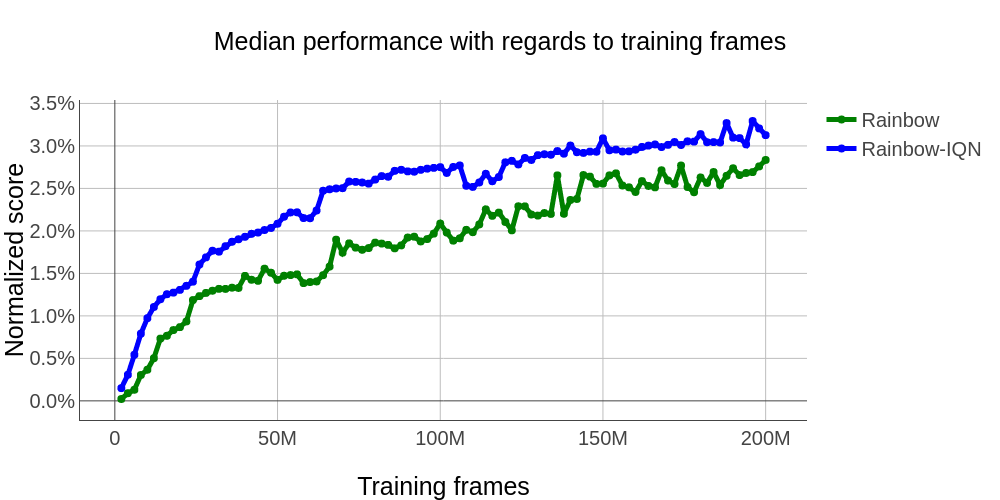

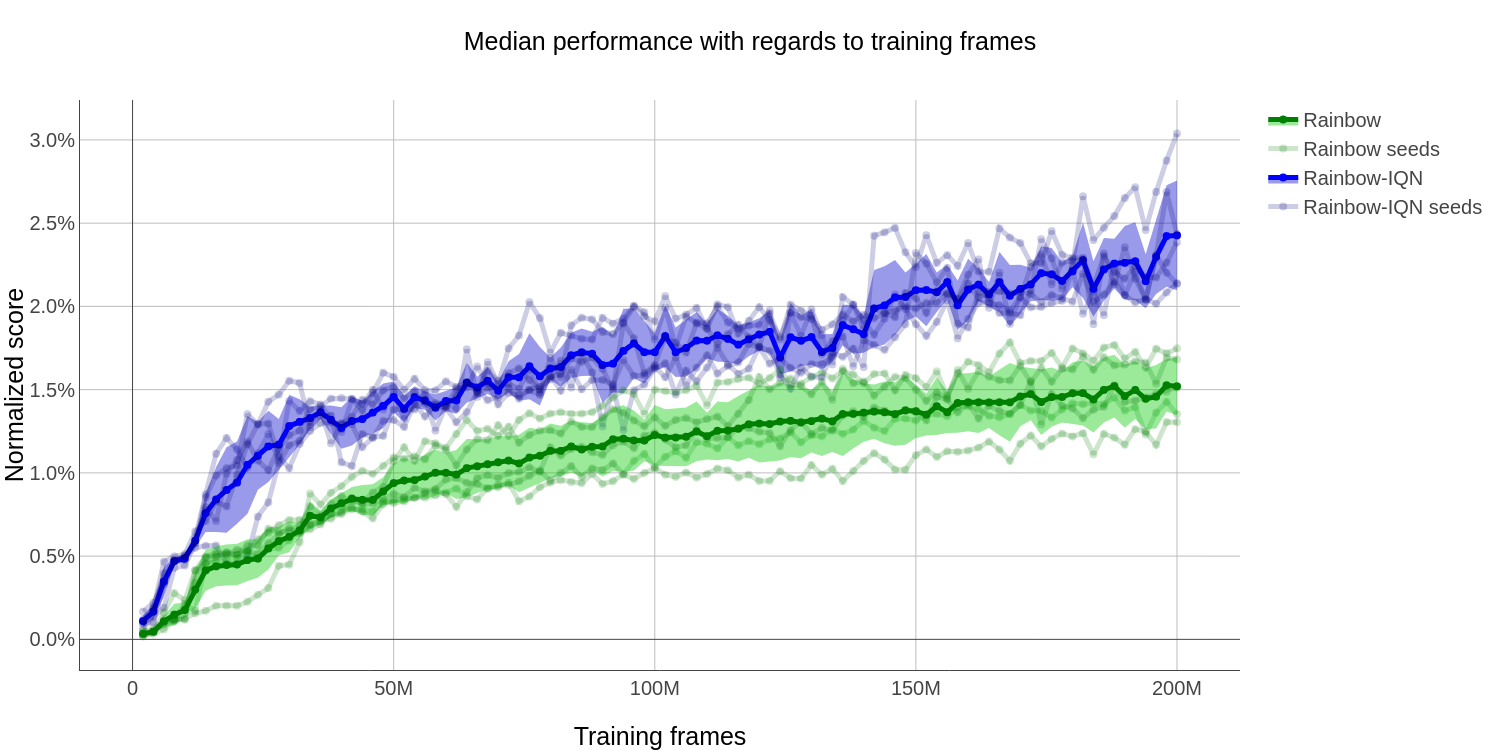

As shown in the graph below, R-IQN outperforms Rainbow and thus becomes the new state-of-the-art on Atari. However, we acknowledge that in order to make a more confident state-of-the-art claim we should run multiple times with different seeds. Testing an increased number of random seeds across the 60 Atari games is a computationally costly endeavor and is beyond the scope of this study. We test the stability of the performances of R-IQN across 5 random seeds on a subset of 14 games. We compare against Rainbow and report similar results in Figure 3.

Open-source implementation of distributed Rainbow-IQN: R-IQN Ape-X

We release our code of a distributed version of Rainbow-IQN following ideas from Ape-X (Horgan et al., 2018). The distributed part is our main practical advantage over some existing DRL repositories (particularly Dopamine a popular open-source implementation of DQN, C51, IQN and a small-Rainbow but in which all algorithms are single worker). Indeed, when using DRL algorithms for other tasks (other than Atari and MuJoCO) a major bottleneck is the speed of the environment. DRL algorithms often need a huge amount of data before reaching reasonable performance. This amount may be practically impossible to reach if the environment is real-time and if collecting data from multiple environments at the same time is not possible.

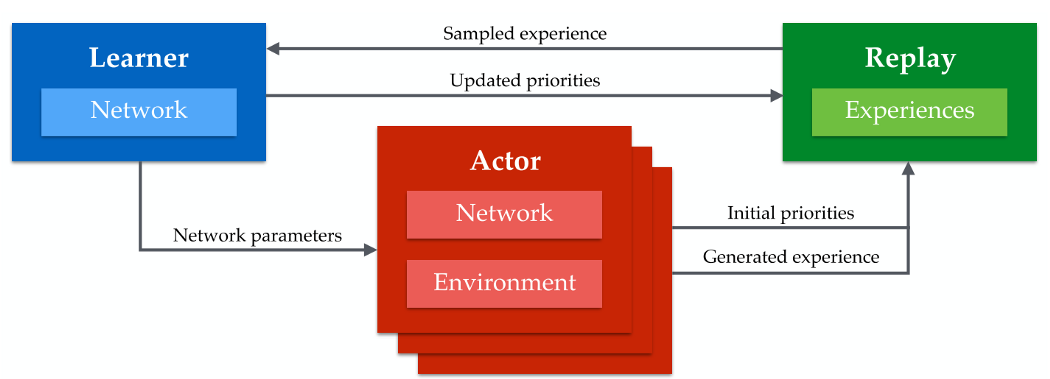

Building upon ideas from Ape-X, we use REDIS as a side server to store our replay memory. Multiple actors will act in their own instances of the environment to fill as fast as they can the replay memory. Finally, the learner will sample from this replay memory (the learner is actually completely independent of the environment) for backprop. The learner will also periodically update the weight of each actor as shown in the schema below.

This scheme allowed us to use R-IQN Ape-X for the task of autonomous driving using CARLA as environment. This enabled us to win the CARLA Challenge on Track 2 Cameras Only showing the strength of R-IQN Ape-X as a general algorithm.

Conclusion

In this work, we confirm the impact of standardized guidelines for DRL evaluation, and build a consolidated benchmark, SABER. In order to provide a more significant comparison, we build a new baseline based on human world records and show that the state-of-the-art Rainbow agent is in fact far from human world record performance. In the paper we share possible reasons for this failure. We hope that SABER will facilitate better comparisons and enable new exciting methods to prove their effectiveness without ambiguity.

Check out our paper to find out more about intuitions, experiments and interpretations.

References

- Matteo Hessel, Joseph Modayil, Hado Van Hasselt, Tom Schaul, Georg Ostrovski, Will Dabney, Dan Horgan, Bilal Piot, Mohammad Azar, and David Silver. Rainbow: Combining improvements in deep reinforcement learning. In AAAI, 2018.

- Will Dabney, Georg Ostrovski, David Silver, and Rémi Munos. Implicit quantile networks for distributional reinforcement learning. In ICML, 2018.

- Marlos C Machado, Marc G Bellemare, Erik Talvitie, Joel Veness, Matthew Hausknecht, and Michael Bowling. Revisiting the arcade learning environment: Evaluation protocols and open problems for general agents. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 2018.

- John Schulman, Filip Wolski, Prafulla Dhariwal, Alec Radford, and Oleg Klimov. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347, 2017.

- Marc G Bellemare, Will Dabney, and Rémi Munos. A distributional perspective on reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06887, 2017.

- Dan Horgan, John Quan, David Budden, Gabriel Barth-Maron, Matteo Hessel, Hado Van Hasselt, and David Silver. Distributed prioritized experience replay. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.00933, 2018.